Anwar Ibrahim |

- Flight MH370: lost jet exposes gaps in Malaysia’s defences

- Planet Plutocrat

- Mishaps Mar Malaysia’s Handling of Flight Tragedy

- Wan Azizah: Is everything Anwar’s fault?

| Flight MH370: lost jet exposes gaps in Malaysia’s defences Posted: 17 Mar 2014 02:33 AM PDT Allies and neighbours concerned after prime minister discloses flight MH370 crossed its territory without being picked up by military radarMalaysia has rejected questions over its air defence systems following the seizure and disappearance of flight MH370 and claimed the lessons learned from the crisis could "change aviation history". The disclosure by Prime Minister Najib Razak that the Malaysia Airlines plane was seized shortly after taking off from Kuala Lumpur, turned around over the South China Sea and flew back over Peninsular Malaysia without alerting the country's defence forces has caused alarm among neighbours and allies. After the September 11 2001 attacks on the United States, air defences across the world were tightened and new procedures adopted to speed the detection of rogue aircraft and intercept them before they could be used as weapons of terrorism. But the apparent failure of Malaysia, which has a defence agreement with Britain, to notice that the plane had changed direction, fallen off the radar and then flown towards and through its air space has identified serious loopholes in its air defences. Most countries with advanced air forces would detect an incoming hostile aircraft 200 miles from shore and scramble fighter jets to challenge it. There has been strong criticism of the failure in China, India and in private by Western diplomats and defence analysts. A Western security source said while the current focus is on helping Malaysia locate the missing plane, "there are a lot of questions – how did it get to the point where it came back and went wherever? You would have thought [planes] would have been scrambled and the Malaysians would have acted." Sugata Pramanik, an Indian air traffic controllers' leader, said a plane can "can easily become invisible to civilian radar by switching off the transponder … But it cannot avoid defence systems." One senior Indian Navy commander, Rear Admiral Sudhir Pillai, however said his country's military radars were occasionally "switched off as we operate on an ‘as required' basis". The Royal Malaysian Air Force is widely respected and has a fleet of Sukhoi S30 and F16 fighter jets and does regular training exercises with their British, Australian, New Zealand and Singapore counterparts. Malaysia's Transport Minister Hishammuddin Hussein however dismissed the concerns and said the disaster was an "unprecedented case" with lessons for all. "It's not right to say there is a breach in the standard procedures … what we're going through here is being monitored throughout the world and may change aviation history," he said. His comments were supported by Azharuddin Abdul Rahman, Malaysia's Director General of Civil Aviation, who said "many will have lessons to learn from this. I've been in aviation for 35 years and I've never seen this kind of incident before". Neither elaborated on the loopholes exposed beyond Malaysia by the seizure of MH370 and stressed that Kuala Lumpur would not focus on the issue until it had found the aircraft and its passengers on crew. Anifah Aman, Malaysia's foreign minister, told The Telegraph the world was "missing the point" by focusing on security implications and that he still hoped for a ‘miracle' in finding the passengers and crew alive. "The focus must be on finding the plane. I don't want to support any of the theories at this juncture. This involves a lot of lives. My worry is where is the plane and what little chance that people are safe so that they can come back … we believe in miracles and like to think they're safe and can return to their families," he said. The prime minister confirmed on Saturday that the Boeing 777 had been flown from close to Vietnamese air space over the South China Sea, back across the Malaysian peninsula to the Strait of Malacca, close to Penang, and then took two possible navigational corridors. Search operations, now including 25 countries, are now focused on a northern corridor from the Turkmenistan-Kazakhstan border to northern Thailand and a southern sector from Indonesia to the vast southern Indian Ocean. The investigation into what happened to the plane is now based on four theories – all of which follow from Mr Najib's acceptance on Saturday that the plane had been deliberately seized or hijacked. Police Inspector General Khalid Abu Bakar said those who had taken the plane were either hijackers, saboteurs, someone with a personal vendetta or a psychological problem. His investigation had been launched under a Malaysian law which covers terrorism offences, he said. Until now the government has been reluctant to refer to the seizure as a hijacking or act of terrorism because they have yet to find any evidence on the motive of whoever seized the plane on Saturday March 8th. The minister and the police chief's comments however marked a freer use of the terms following the prime minister's confirmation that the plane had been deliberately taken and re-routed. Malaysia has not suffered terrorism on the scale of neighbours Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines, although several Malaysian nationals are known to have received training from al-Qaeda.

|

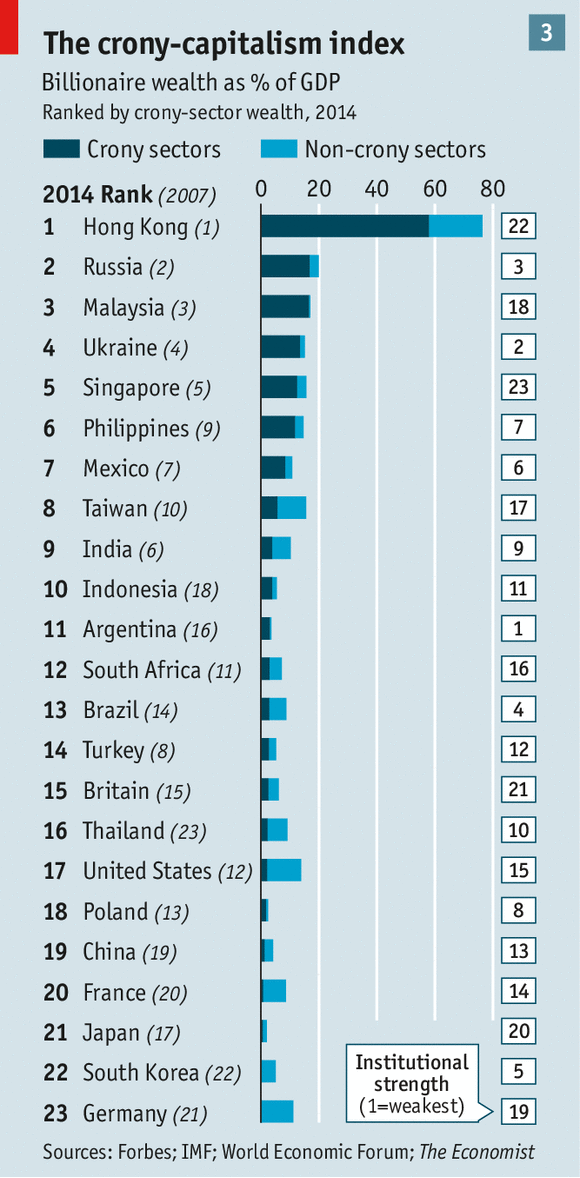

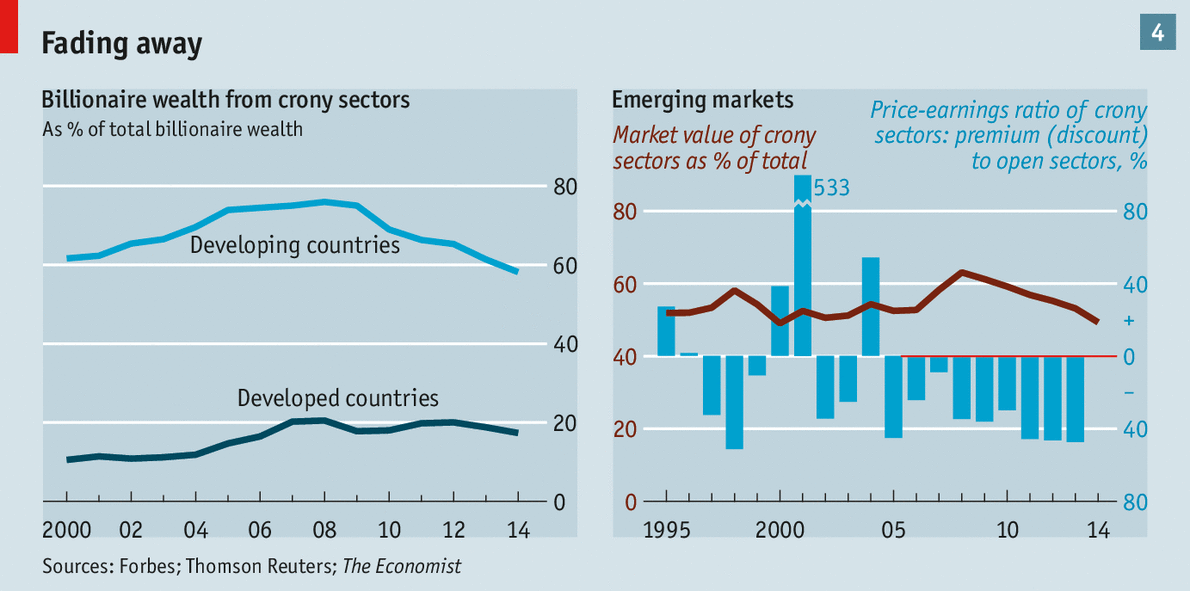

| Posted: 17 Mar 2014 02:27 AM PDT The countries where politically connected businessmen are most likely to prosperAMERICA'S Gilded Age, in the late 19th century, saw tycoons such as John D. Rockefeller industrialise the country—and accumulate vast fortunes, build palatial mansions and bribe politicians. Then came the backlash. Between 1900 and 1945 America began to regulate big business and build a social safety net. In her book "Plutocrats", Chrystia Freeland argues that emerging markets are now experiencing their first gilded age, and rich countries their second, with the world's wealthiest 1%, who benefited disproportionately from 20 years of globalisation, forming a "new virtual nation of Mammon". Inventing a better widget, tastier snack or snazzier computer program is one thing. But many of today's tycoons are accused of making fortunes by "rent-seeking": grabbing a bigger slice of the pie rather than making the pie bigger. In technical terms, an economic rent is the difference between what people are paid and what they would have to be paid for their labour, capital, land (or any other inputs into production) to remain in their current use. In a world of perfect competition, rent would not exist. Common examples of rent-seeking (which may or may not be illegal) include forming cartels and lobbying for rules that benefit a firm at the expense of competitors and customers. Class warriors and free-market devotees alike are worrying about rent-seeking. American libertarians fear an elite has rigged their country's economy; plenty of ordinary Joes reckon the government and Federal Reserve care more about Wall Street than Main Street. Many hedge-fund managers sniff that China is a house of cards built by indebted cronies. To test the claim that rent-seekers are on the rampage, we have created a crony-capitalist index. Our approach builds on work by Ruchir Sharma of Morgan Stanley Investment Management, Aditi Gandhi and Michael Walton of New Delhi's Centre for Policy Research, and others. We use data fromForbes to calculate the total wealth of those of the world's billionaires who are active mainly in rent-heavy industries, and compare that total to world GDP to get a sense of its scale. We show results for 23 countries—the five largest developed ones, the ten largest developing ones for which reliable data are available, and a selection of eight smaller ones where cronyism is thought to be a big problem. The higher the ratio, the more likely the economy suffers from a severe case of crony-capitalism.  We have included industries that are vulnerable to monopoly, or that involve licensing or heavy state involvement (see table 1). These are more prone to graft, according to the bribery rankings produced by Transparency International, an anti-corruption watchdog. Some are obvious. Banks benefit from an implicit state guarantee that lowers their cost of borrowing. When publicly owned coal mines, land and telecoms spectrum are handed to tycoons on favourable terms, the public suffers. But the boundary between legality and graft is complex. A billionaire in a rent-heavy industry need not be corrupt or have broken the law. Industries that are close to the state are still essential, and can be healthy and transparent. A galaxy of riches  Billionaires in crony sectors have had a great century so far (see chart 2). In the emerging world their wealth doubled relative to the size of the economy, and is equivalent to over 4% of GDP, compared with 2% in 2000. Developing countries contribute 42% of world output, but 65% of crony wealth. Urbanisation and a long economic boom have boosted land and property values. A China-driven commodity boom enriched natural-resource owners from Brazil to Indonesia. Some privatisations took place on dubious terms.  Of the world's big economies, Russia scores worst (see chart 3). The transition from communism saw political insiders grab natural resources in the 1990s, and its oligarchs became richer still as commodity prices soared. Unstable Ukraine looks similar. Mexico scores badly mainly because of Carlos Slim, who controls its biggest firms in both fixed-line and mobile telephony. French and German billionaires, by contrast, rely rather little on the state, making their money largely from retail and luxury brands. America scores well, too. The total wealth of its billionaires is high relative to GDP, but was mostly created in open sectors. Silicon Valley's wizards are far richer than America's energy billionaires. It is one of the few countries where rent-seeking fortunes grew only in line with the economy in recent years, which explains its improved position since 2007. Despite concerns about vampire-squid financiers, few of its billionaires made their money in banking. Even including private equity as rent-seeking, on the grounds that it benefits from tax breaks and cheap loans, would make little difference. Compared with Larry Ellison of Oracle, Stephen Schwarzman of Blackstone is a pauper. Countries that do well on the crony index generally have better bureaucracies and institutions, as judged by the World Economic Forum. But efficient government is no guarantee of a good score: Hong Kong and Singapore are packed with billionaires in crony industries. This reflects scarce land, which boosts property values, and their role as entrepots for shiftier neighbours. Hong Kong has also long been lax on antitrust: it only passed an economy-wide competition law two years ago. Another surprise is that despite its reputation for graft, mainland China scores quite well. One reason is that the state owns most natural resources and banks; these are a big source of crony wealth in other emerging economies. Another is that China's open industries have fostered a new generation of fabulously rich entrepreneurs, including Jack Ma of Alibaba, an e-commerce firm, and Liang Wengen of Sany, which makes diggers and cranes. One of the most improved countries is India, which moved from sixth place in our ranking to ninth. Recent graft scandals and a slowing economy have hurt many of its financially leveraged and politically connected businessmen, while those active in technology, pharmaceuticals and consumer goods have prospered. Turkish billionaires in rent-seeking industries have been hit by their country's financial turmoil. By contrast most countries in South-East Asia, including Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines, saw their scores get worse between 2007 and 2014, as tycoons active in real estate and natural resources got richer. Who are you calling a crony? Our crony index has three big shortcomings. One is that not all cronies make their wealth public. This may be a particular problem in China, where recent exposés suggest that many powerful politicians have disguised their fortunes by persuading friends and family to hold wealth on their behalf. Unreliable property records also help to disguise who owns what. Second, our categorisation of sectors is crude. Rent-seeking may take place in those we have labelled open, and some countries have competitive markets we label crony. Some think America's big internet firms are de-facto monopolies that abuse their positions. South Korea's chaebol, which sell cars and electronics to the world, are mainly in industries we classify as open. But they have a history of bribing politicians at home. China's billionaires, in whatever industry, are often chummy with politicians and get subsidised credit from state banks. According to Rupert Hoogewerf of the Hurun Report, a research firm, a third are members of the Communist Party. Sectors that are cronyish in developing countries may be competitive in rich ones: building skyscrapers in Mumbai is hard without paying bribes, and easy in Berlin. Our index does not differentiate. The third limitation is that we only count the wealth of billionaires. Plenty of rent-seeking may enrich the very wealthy who fall short of that cut-off. America's subprime boom saw hordes of bankers earn cumulative bonuses in the millions of dollars, not billions. Crooked Chinese officials may have Range Rovers and secret boltholes in Singapore—but not enough wealth to join a list of billionaires. So our index is only a rough guide to the concentration of wealth in opaque industries compared with more competitive ones. Despite the boom in crony wealth, there are grounds for optimism. Some countries are tightening antitrust rules. Mexico has many lucrative near-monopolies, from telecoms to food, but its government is at last aiming to improve regulation and boost competition. India's legal system is trying to jail a minister accused of handing telecoms licences to his chums.  Encouragingly, there are also hints that cronyism may have peaked. The share of billionaire wealth from rent-seeking industries has declined in developing countries, from a high of 76% in 2008 to 58% (see chart 4). That partly reflects lower commodity prices. But now that emerging markets are slowing, investors are becoming pickier. More are steering clear of firms in opaque industries with bad governance. The price-earnings ratio of firms in crony sectors is now at its biggest discount to firms in open sectors for 15 years. That suggests that the highest returns to outside investors are to be found in open industries. Perhaps when growth picks up again in emerging markets, rent-seeking will explode once more. Or, as countries get richer, the share of great wealth that is made in crony industries may naturally decline. In 1900 American tycoons became rich by building and financing railroads. By 1930 the action had shifted to food production, photography and retailing. Cronies around the world should take note. |

| Mishaps Mar Malaysia’s Handling of Flight Tragedy Posted: 17 Mar 2014 02:22 AM PDT Miscues and media gaffes are turning Malaysia into an object of anger and criticism in the aftermath of the disappearance early Saturday morning of a Malaysian Airlines jetliner carrying 239 passengers and crew. No trace of the craft has been found despite a search encompassing thousands of square kilometers. On Wednesday, the day was dominated by confusion over reports that the aircraft might have attempted to head back toward Malaysia before it disappeared. Malaysia's air force chief told reporters very early Wednesday that the plane had veered off course. Later in the morning, the same officer denied the report sharply. By Wednesday afternoon, the government seemed to reverse itself again, requesting assistance from India in searching the Andaman Sea, north of the Malacca Strait, where the plane may have gone down far from the current search area off the coast of Vietnam. Officials finally said the plane “may” have been heading toward the Strait of Malacca when it disappeared and that the search was now also concentrated in that area. Other countries have grown frustrated. The Chinese, with 152 passengers on board, have complained about a lack of transparency over details. They have also complained that Malaysian Airlines staff handling relatives of the victims in Beijing have been short of information and in many cases don't speak Mandarin. From the start, according to critics, the Malaysians have treated the disappearance and ensuing inconsistencies as a local problem instead of one that has focused the attention of the entire world's media on the tragedy. In a semi-democratic country with a largely supine domestic media, the government insists it has the situation in hand but that hardly seems the case. Often, those giving press briefings about the affair communicate badly in English to an international press whose lingua franca is English. Because of widely differing reports of where the aircraft actually disappeared, the picture being delivered is one of incompetence. Networks like the BBC and CNN are openly declaring that the post-accident situation is a mess. Some of it isn't Malaysia's fault. An initial report that two possible hijackers using fake passports somehow got through the country's passport control because of lax surveillance turned out to be false. While the two were traveling on false passports, apparently the stolen documents had never been reported to Interpol, which tracks such incidents. The pair turned out to be Iranians seeking asylum in Europe. But that wasn't helped by the fact that Malaysian authorities originally said erroneously that as many as four to five people could have been traveling with suspect passports, raising the possibility of a fully-fledged hijack gang aboard. But five days into the loss of the aircraft and with no idea of where it could have disappeared, there is growing concern over who is in charge, coupled with the fact that Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak has largely removed himself from the picture, allowing his cousin, Hishammuddin Hussein, the defense minister and acting transport minister, to deal with the affair. International treaties that allow for Malaysia to greatly expand the probe by calling in experts from foreign governments to help were not invoked until Wednesday, it seems, when it was reported that US and other foreign experts had finally been invited to take part in the formal investigation. It seemed again that valuable time had been lost. Much of the problem is due to the fact that the Malaysian government has habitually handled information as a problem rather than as a means of communication. The mainstream news media are all owned by the ruling political parties and are used to being fed information the government wants them to hear. Government-owned MAS at one point issued a press release only to recall it twice because of misspellings and misinformation. In a deeply divided political culture, especially in the last year as the opposition has grown more effective, the government is finding it difficult to manage the flow of information on a disaster. In addition, in the midst of this flight crisis the government is seeming preoccupied by court actions to drive two opposition leaders, Anwar Ibrahim of Parti Keadilan Rakyat, and Karpal Singh of the Democratic Action Party, out of Parliament. At the start, the plane was characterized as having simply gone off the radar – until Wednesday, when a report carried in Berita Harian, a government-controlled Malay-language newspaper, quoted Air Force chief Gen. Rodzali Daud as saying Malaysian radar had tracked the missing Boeing 777-200 turning left from its last known location on radar. It then supposedly crossed Malaysia itself and disappeared over the Strait of Malacca. The report set off a frenzy. CNN and the BBC carried maps of the new possible crash site as it was reported that the massive search for the wreckage had shifted to the waters between Malaysia and Indonesia instead of the South China Sea off the coast of Vietnam. Then the report was emphatically denied by Daud, who told a press conference that “I wish to state that I did not make any such statements as above." CNN, however, quoted an unnamed "senior air force source" as saying the plane indeed had shown up on radar for more than an hour after contact was lost at around 1:30 a.m. Saturday. The craft was last detected, according to the official, near Pulau Perak, a small island in the Strait of Malacca. Has four days been wasted by a huge flotilla of airplanes and ships that have been scouring the South China Sea for wreckage while the plane might actually be somewhere 900 km. to the west? The Vietnamese announced they were suspending their participation in the search. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang on Tuesday complained about the lack of progress in finding the plane, saying "We once again request and urge the Malaysia side to enhance and strengthen rescue and searching efforts." The Chinese government itself is starting to feel the heat, offering to deploy 10 satellites in the effort to find the plane. The crisis wasn't helped any by a sensational revelation from Australia by a young South African woman that she and a friend had once ridden in the cockpit of an MAS flight from Phuket to Kuala Lumpur at the invitation of the missing co-pilot, Fariq Abdul Hamid, and had pictures of themselves flirting with the pilots, who were even smoking in the cockpit, to prove it. Since 9/11 in the United States, airline regulations forbid anyone not part of the crew from gaining access to the cockpit. If nothing else, the story and the pictures are an indication of lax flight deck discipline and raise questions if someone could have got into the pilots' cabin aboard MH370. |

| Wan Azizah: Is everything Anwar’s fault? Posted: 17 Mar 2014 02:13 AM PDT In questioning a news report which linked the pilot of MH370 to her husband, PKR president Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail asked: “Is everything Anwar’s fault?”. She was responding to UK tabloid Daily Mail‘s report that Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, a PKR member, is a “political fanatic”. “There are many PKR members. They say Captain Zaharie cried over the (sodomy) verdict. Millions of other Malaysians did so, too," Wan Azizah said. Daily Mail had reported that Zaharie (right) was in court when the verdict with regard to Anwar Ibrahim's conviction was delivered less than 24 hours before MH370 took off from KLIA at 12.41am on March 8. Berita Harian also published a column floating the theory that the mysterious disappearance had to do with claims that most MAS pilots support Pakatan Rakyat. Wan Azizah also denied that Pakatan is politicising the disappearance of MH370 but was merely criticising what seemed to be poor crisis management on the part of the government. “We sympathise with the victims but we criticise how the government has handled this crisis. We are not politicising it. BN leaders had urged Pakatan to stop politicising the missing Malaysia Airlines’ aircraft on the campaign trail. Meanwhile, PKR Kajang by-election director Abdul Khalid Ibrahim said the party does not dispute that Zaharie is a PKR lifetime member. “It means he paid the party RM200. Just like I did,” he added. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Anwar Ibrahim To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |